Does Reshoring Make Sense for Generics?

There is no silver bullet for fixing the generics supply chain

The other night, to the chagrin of my partner, I spent a solid five minutes researching the brand of the hand sanitizer at the local restaurant. All this fuss started when I worked at a chemical company known for its high-quality hand sanitizer. Yet, curiously, until recently I paid no attention to the brand of the medication I’d been taking for hypothyroidism, a prevalent condition in the US.

Like most people, I assumed that the drug was safe and would remediate my condition. I’ve also never had a trouble finding my medication in both urban and rural areas of the country as I travel frequently for work and often forget to take my medication along with me. Finally, the cost of the prescription is reasonable—about $20 for a 3-month supply.

But, as I recently learned, many patients across the United States don’t have this luxury. Indeed, access to many critical generics prescribed to treat a range of conditions, from life threatening diseases like lung cancer to seasonal illnesses such as strep throat, has gotten worse over the last couple of years due to persistent supply shortages and vulnerabilities across the supply chain, which were laid stark after the COVID-19 pandemic.

And in addition to supply shortages, quality issues persist within the industry, which creates further uncertainty for patients and doctors alike.

The result is that the generics supply has become a national security priority for the United States. And given that many of the issues around supply and quality are inextricably linked with the globalization of the generics supply chain, the Biden administration has highlighted boosting local production of generics as a key intervention to combat issues such as:

The complexity, vastness, and multinational nature of drug supply chains and the corresponding overdependence on foreign entities who may prioritize national interests above trade in an emergency

Lack of redundant capacity in manufacturing

Reduced incentives for existing manufacturers to invest in upgrading equipment, improving supply chains, or expanding capacity

The question is whether deploying subsidies to spur generics manufacturing will be worth the squeeze given the high potential cost. Is it worth pursuing a similar strategy to the semi-conductor sector where the Biden Administration’s CHIPS Act has earmarked $39 Billion in Federal subsidies for new semi-conductor plants in the United States?

At a high level, it is intuitive that the closer a product is to home, the easier it is to control it. But reshoring generics could also lead to some deleterious results, from reduced overall quantities of generics on the market, due to exits of foreign manufacturers, to significantly higher prices for drugs.

What are the alternatives? I will explore that later, but first let me explain how we got here.

How We Got Here

In theory firms should be able to re-create a drug so long as they have the formula and the means to manufacture it. This fact, along with the desire to reduce costs for patients (the AIDs epidemic was a major driver for the push for generics), led to the passage of Hatchman-Waxman act in 1984, which codified the view that generics and brand name drugs are perfectly substitutable (clinically referred to as bioequivalence), which in turn significantly eased the process for obtaining regulatory approval for new drugs.

Since then, new applications for generics have grown exponentially, with manufacturing firms in emerging markets such as China and India now dominating the supply base. For example, the number of Chinese based Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) manufacturers registered with the FDA more than doubled from 188 to 445 between 2010 and 2015. What’s more, the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR) estimates that almost 95% of sterile injectable (drugs used for acute care) generics now rely on critical materials from China and India.

The globalization of generics manufacturing has created two key challenges. The first concerns quality. As outlined in Katherine Eban’s gripping book “Bottle of Lies,” a race to the bottom for drug prices has sharply increased the variance in drug quality.

The primary case study that Eban cites is Ranbaxy, an Indian manufacturer, one of the first producers of an off-brand anti-viral for AIDS, which eventually fell from grace after several whistleblowers exposed the firm for a host of fraudulent activity, from faked drug quality test data to forged drug applications. While this case study was particularly egregious, it is certainly no anomaly.

Through several case studies the book lays bare the logistical and political challenges that regulators face as they attempt to monitor foreign manufacturers. For example, Eban outlines that while inspections in American plants are as a protocol unannounced, inspections at foreign manufactures are typically announced well in advance, due to a desire to maintain cordial relations with foreign governments. These challenges are further exacerbated by poor or non-existent data on the pharmaceutical supply chain, and a dearth of specially trained government inspectors who are willing to travel to remote manufacturing sites across the world.

The second key challenge for generics is supply resiliency in the face of shocks. This is best outlined in a new job market paper out of Princeton by Anais Galdin, which analyzes the effect of offshoring a generics drug on the probability of a shortage of that drug. Specifically, Galdin finds that generics that are offshored are 12% more likely to experience a shortage than similar drugs that continue to be manufactured in the United States. What’s more, she finds that shortage periods for offshored generics drugs last on average 125 days longer than shortage periods for drugs that were never offshored.

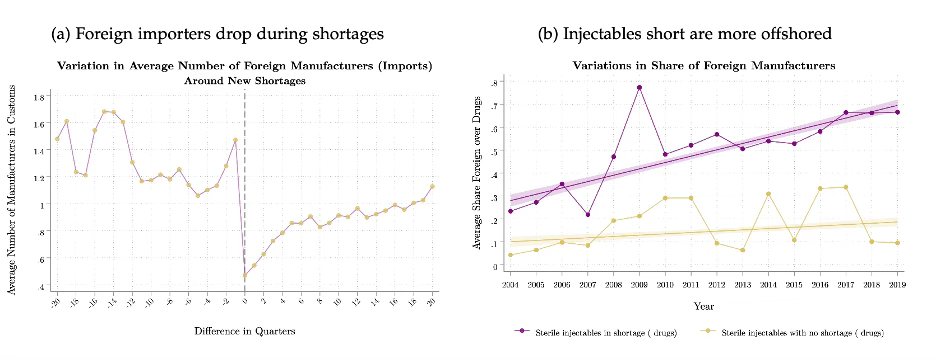

Indeed, two charts from Galdin’s study shown below best illuminate the challenge with offshoring generics. Chart (a) on the left shows that after a drug shortage event, the number of drugs in customs drops sharply. And chart (b) shows that for sterile injectable drugs, there is a strong correlation between the share of foreign manufacturers producing the drug and whether a drug has experienced a shortage or not.

Is Reshoring the Right Solution for Generics?

As stated earlier, one of the Biden Admin’s supply chain resiliency task force’s key priorities is to boost domestic production of generics and semiconductors. At a high level the policy goal for both sectors is to secure the supply of products that are critical to national security and reduce the USA’s dependence on foreign manufacturers.

With regards to semiconductors, I can see some merit in reshoring. For one, semiconductor manufacturing is highly complex, making it a sector with high barriers to entry—this is good. Reshoring will also likely spur further innovation in chip manufacturing, boost adjacent industries, and perhaps most importantly, reduce the United States’ reliance on Taiwan, a country that could soon come under the direct influence of China.

This is not to say that turning the USA into semi-conductor manufacturing hub will be easy. For example, one key concern is that the US will not have the requisite talent to support semiconductor manufacturing plants as they come online.

However, I find it hard to make the same argument for reshoring the manufacturing of generics. For one, while some generics are complex to manufacture, they do not represent a cutting-edge industry. Put another way, an optimal industry policy strategy should aim to promote investment into innovation and novel products (e.g., branded bio-pharma products) rather than subsidize non-leading-edge sectors such as generics. Second, unlike the semi-conductor supply chain, which has become almost entirely dependent on Taiwan (90% of advanced chips are made in Taiwan) as a manufacturing base, the generics supply chain is more dispersed across emerging markets.

Instead, policymakers would be better off focusing on interventions to:

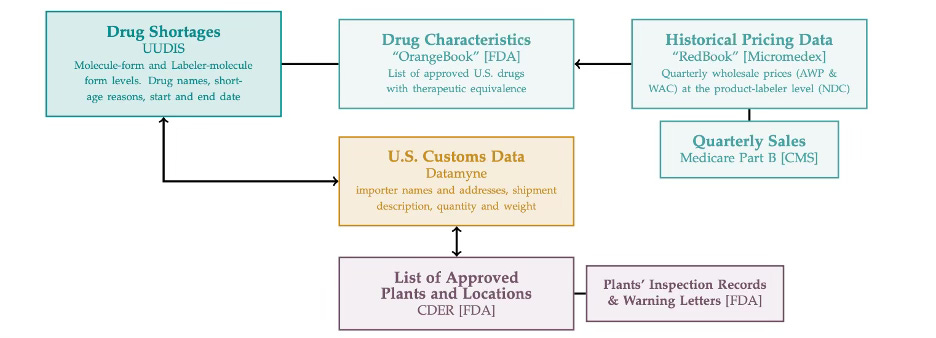

Increase transparency in the bio-pharma supply chain for regulators and firms alike This would make monitoring, evaluating, and preparing for shortage events in the supply chain simpler for government agencies and firms. Indeed, this is best exemplified in the complex mapping exercise that Galdin had to go through to undertake her analysis on shortages in the generics market:

Look beyond price when purchasing generics

Currently prices set by Group Pharmacy Organizations (GPOs) for generics are fixed, even during a shortage. Instead, a policy to set a market clearing price during a shortage would incentivize firms to hold more buffer stock.

Second, a pure focus on price when purchasing generics can often lead to deals with manufacturers with poor quality control. What’s more, such a policy is anti-competitive. Indeed, a working paper from 2017 found that 40% of generics markets are supplied by just one manufacturer. As such, expanding the variables used in purchasing a product beyond price would incentivize more expensive, sustainable and reliable generic brands to enter the market and increase the sphere of competition.

Ramp up Quality Inspections Companies must be upheld to much more rigorous testing standards. In addition, more transparency around quality testing would give consumers and doctors more confidence in generics. In short, further investment here would go a long way, either inside the FDA or through a secondary market subsidized by the Federal Government.

Not only will these interventions take less time to implement than a reshoring strategy, but they will also likely be more cost-effective. Indeed, of the three potential interventions —subsidies for reshoring, shortage penalties and market clearing prices during shortages— Galdin’s study finds reshoring to be the least optimal intervention, leading to both highest increases in generics prices and the largest decreases in generics volume on the market:

Subsidizing reshoring unequivocally results in an increase in the unit price of drug products…..a suggested 10% tax break translates into a 30% increase in prices over injectable markets. A 15 to 20% tax break could lead to up to a 50% increase in price across injectable markets.”