Why Consumers are Still Unhappy and What this Means for 2024

High prices, a persistent COVID-19 hangover and negative media coverage are some of the key drivers of poor consumer confidence as we head into 2024.

Though we have started 2024 on the back of several positive economic trends, consumer sentiment is still in the doldrums. Why is the case and what does it mean for the most important event of 2024?

The Good News

Start with the good. Below are 4 positive economic trends which have made the rounds among economists and pundits at the end of 2023:

While interest rates have climbed and the inflation rate has fallen, employment rates have held *relatively* strong (Figure 1), defying the standard linear Phillips curve model, which assumes a negative and linear relationship between the inflation rate and the unemployment rate: i.e., lowering inflation leading to higher unemployment.

Inflation, which was a major thorn over the last few years, appears to be largely under control in the USA, especially when compared to other Western nations.

Real incomes, particularly for lower income workers, have risen substantially over the last few years.

In 2023 the stock-market had its best year since 2009

In short, average Americans are still spoiled for job choices (though quit rates have slowed and job openings have decreased in the last few months), have seen an improvement in real incomes over the last few years, and have witnessed steady improvements in their 401Ks.

This is best reflected in *real* consumer spending, which has remained strong through all of 2023.

Why So Sad?

But according to the University of Michigan’s November 2023 consumer sentiment survey, which aggregates numerous indexes on consumer perceptions about current and future business conditions, consumer confidence still hasn’t fully recovered to pre-COVID levels. Indeed, the index for consumer sentiment is considerably lower now than it was following the outbreak of COVID.

The COVID Hangover Remains

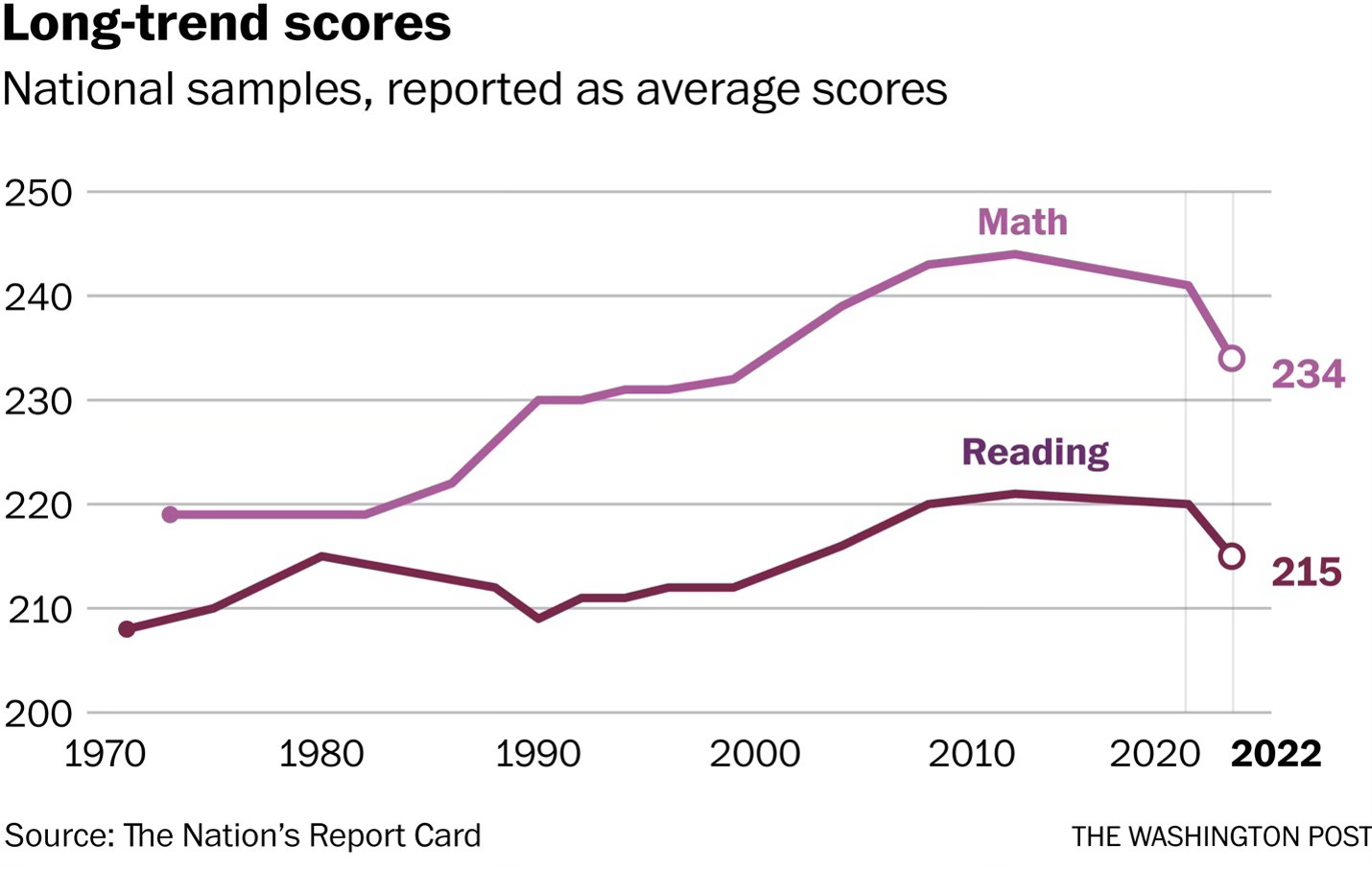

What’s going on here? To start, as argued by former Federal Reserve economist Claudia Sahm, the COVID-19 shock has left behind a trail of long-lasting negative effects and trauma. One prime example of this is the loss in student learning across the United States, which is best illustrated by the precipitous decline in student test scores in math and reading post COVID-19.

Other lingering effects of the pandemic include, but are not limited to, reduced social interaction, increased rates of loneliness and more time spent at home.

Consumers Still Feel the Inflation Shock

The second and most crucial reason why consumers are so gloomy is the simple fact that prices for many goods and services are a lot higher now than they were even 2 years ago. This is best illustrated in Figure 7, which shows that over 40% of Americans listed high prices as a reason for worse personal finances towards the end of 2023.

Indeed, the reason why economists are cheering while laypeople are scowling is that higher prices have yet to become entrenched as “normal” prices. The best example I have of this comes from a friend who works in finance and recently asked me, and I’m paraphrasing here: “if inflation has been tamed then why are prices still so high? Why are they not back at pre-2021 levels?” In a sense, my friend was asking me why the Fed doesn’t pursue a policy of deflation to get back to *normal prices,* a strategy that would have Keynes, who witnessed the post-WW1 Great Britain deflation pain firsthand, shaking his head in his grave…

Such a view of inflation is quite common and exacerbated by another fallacious but widely shared belief: that there is little relationship between inflation and nominal wages. Specifically, Americans don’t understand that an inflationary environment can be a boon to specific segments of the workforce, through the mechanism of increased real wages: i.e. for some households income growth outpaces CPI growth in an inflationary environment.

This fact is laid stark in a late 90s paper by Yale Economist Robert Shiller, where when survey respondents were asked to explain the reasons why their incomes changed over the last five years: “most people spoke of their accomplishments and progress” rather than citing inflation as the primary driver for increases in income.

Simply put, real wage gains are neither a macro-trend that consumers care about nor one that they understand.

Business Conditions, Layoff Fears, and the Media

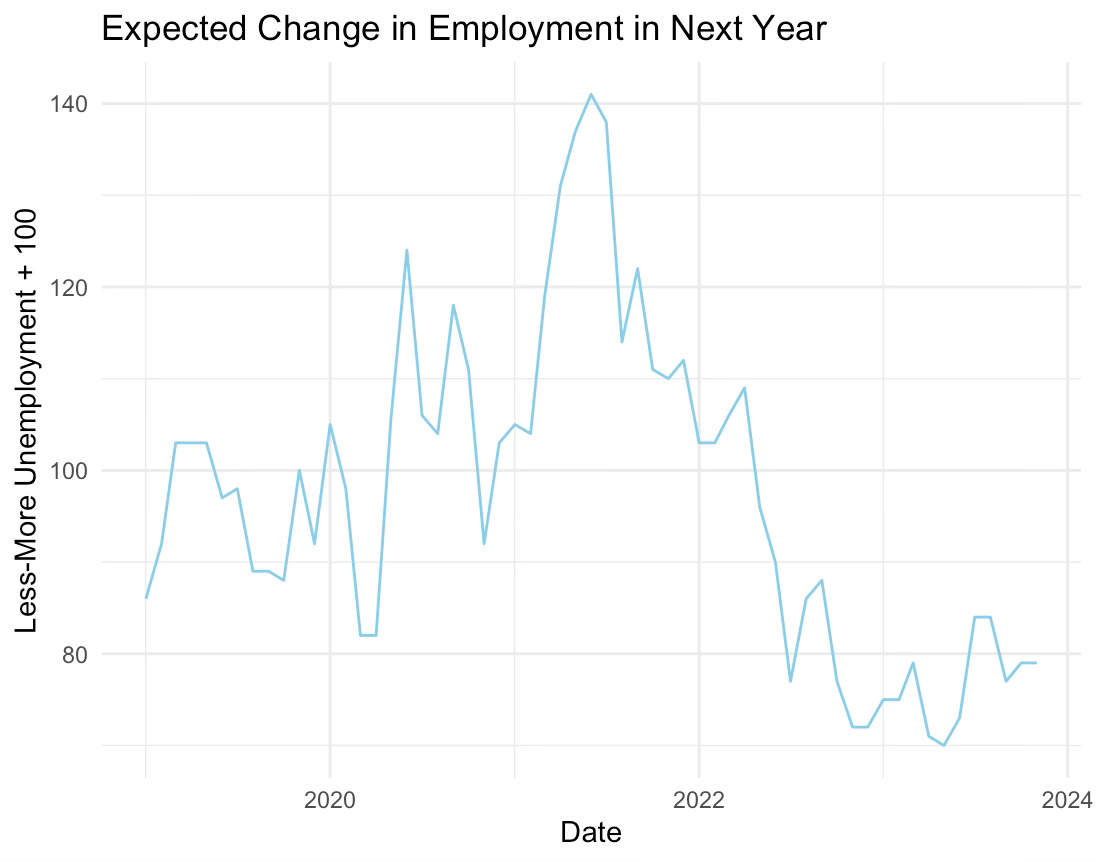

Another interesting driver of low consumer confidence is the public’s expectations of future employment conditions, which was significantly lower in 2023 than at any time in the last decade.

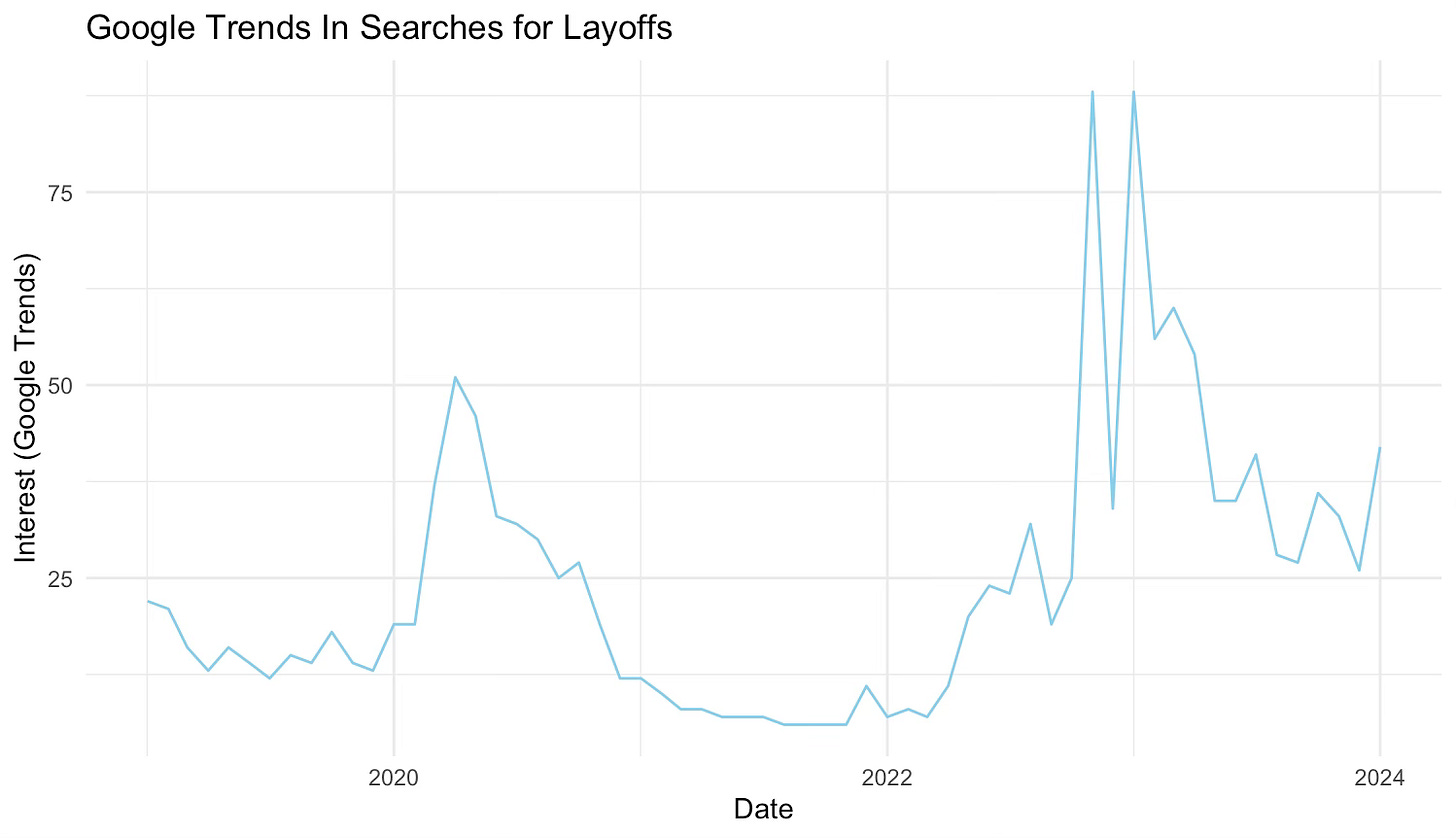

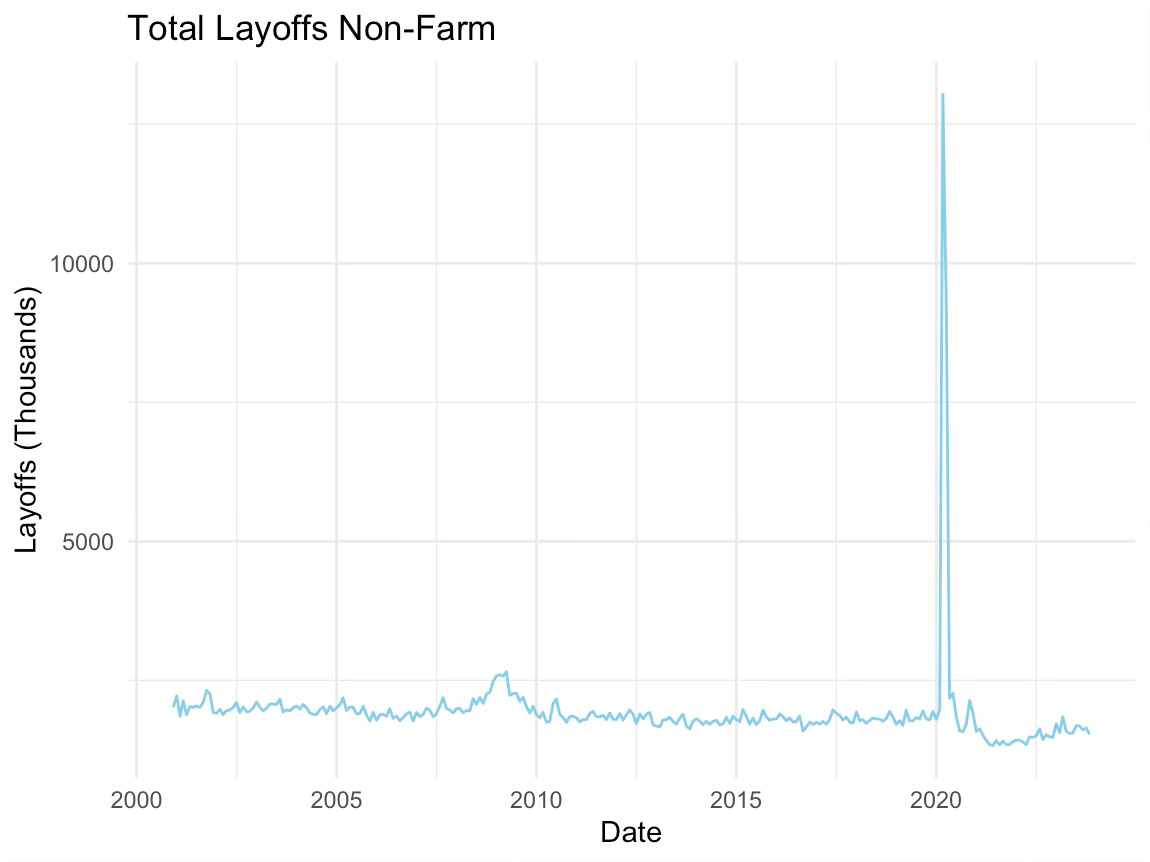

One data point that could be driving this negative sentiment has to do with the 2023 layoffs. Looking at data from Google trends, searches for layoffs were almost twice as high at their peak in 2023 than at any point in the last 5 years. This is surprising because the actual number of layoffs in 2023 was unremarkable.

What’s driving the discrepancy between reality and consumer beliefs? One plausible driver is an increase in news articles on layoffs starting in 2022.

To clarify, the layoffs of 2023 primarily hit the white-collar labor market, which as discussed in a previous post, has experienced a significant slowdown in hiring since late 2021. Specifically, an amalgam of well-known firms such as Google, Twitter and Facebook were among the firms laying off employees by the thousands, which made the layoffs more newsworthy and thus made the idea that layoffs were widespread more prevalent.

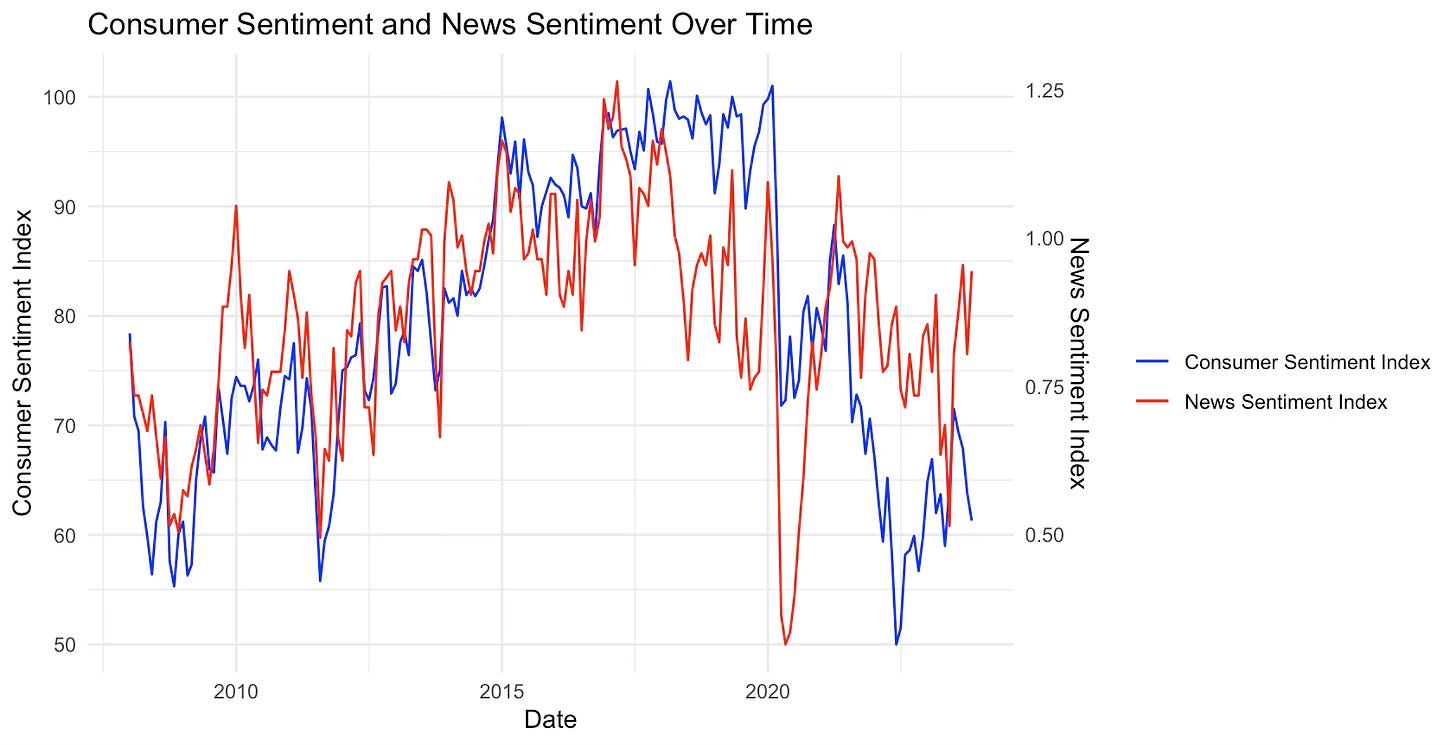

This is not a novel take. Indeed, if we compare the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco’s news sentiment index—a high-frequency measure of economic sentiment based on economics news articles—to the consumer sentiment index, we can see a strong correlation between the two variables over the last decade. And unsurprisingly we see that the news sentiment index was at its lowest point after the beginning of the pandemic in mid 2020.

Such a relationship is particularly concerning in light of recent research showing that news coverage has become “increasingly negative across all states in the past half-century.”

Why Poor Consumer Confidence Matters for 2024: Elections

To summarize the above, consumers have yet to recover from COVID-19 and inflation shocks of the early 2020s. Importantly, it is unclear to what extent the impact of these shocks on consumers will dissipate over the coming year. To further muddy the waters, persistently negative economics media coverage has helped untether consumer confidence from the reality of a strong and resilient economy.

What this means is that further improvements in the macro-economic environment—reduced house prices, interest rates, inflation rate, etc.—may have a limited effect on consumer sentiment.

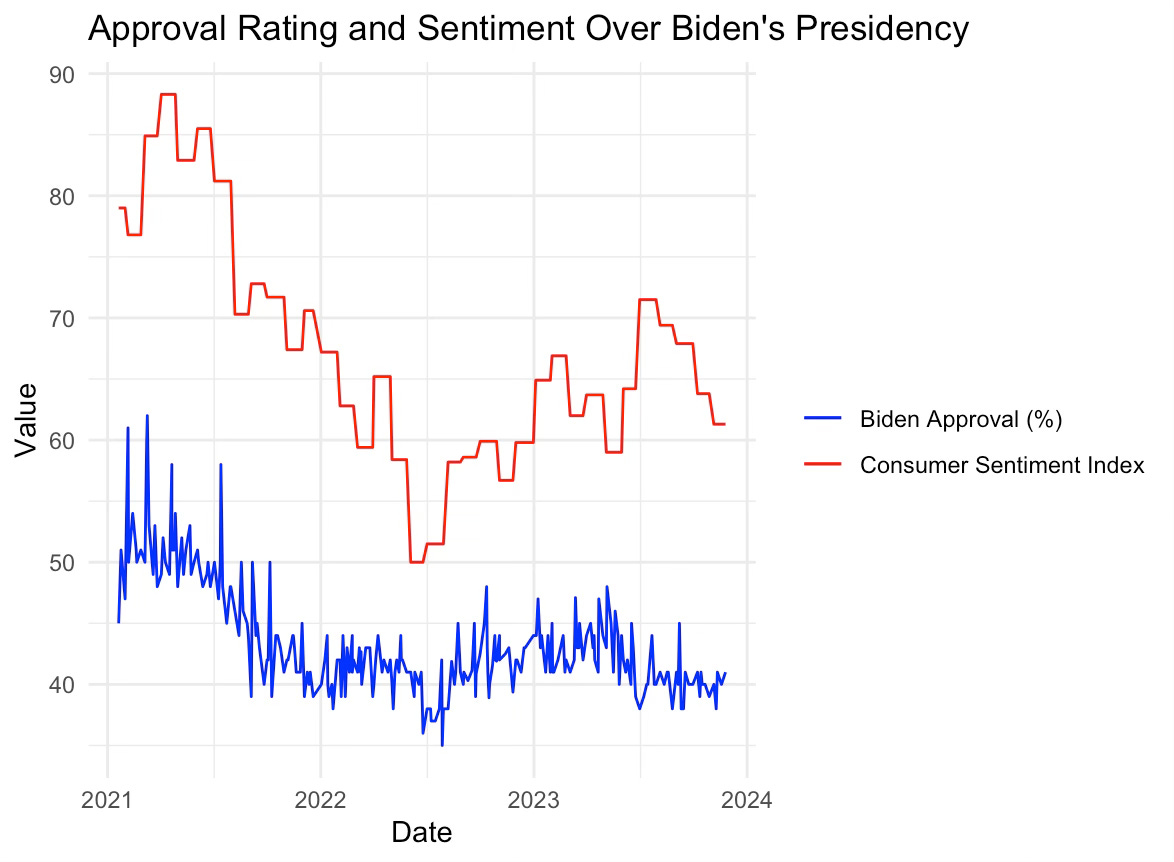

This spells bad news for the Biden campaign as consumer sentiment about current and future business conditions has historically been a strong predictor of the president’s approval rating his/her odds of re-election.

Indeed, looking at data from the start of the Biden presidency I find a positive and statistically significant relationship (p<0.01) between Biden’s approval rating (both YouGov and Quinnipiac polls) and the University of Michigan consumer sentiment index. Specifically, I find that a percentage point increase in consumer sentiment during the Biden presidency leads to a 0.34% percentage point increase in Biden’s approval ratings. Of course, there are many other variables that will affect Biden’s odds of winning the election. What this analysis serves to illustrate is that consumer sentiment should not be discounted as we approach the biggest even of 2024.